(Updated 13/04/2017: Bumped to React Native 0.42.3 and updated code)

One of the cool things I like from working at Badoo (we are hiring!), is that we are free to propose, test and promote new or different techniques, technologies and libraries. React Native has been the buzzword for a while now, but it has recently gained our attention.

Main concerns that came to our mind were the size of the existing codebase (let’s say, sizeable), our highly customised classes to fit our needs and easiness of integration. I decided to test the middle one, and try to write a custom Android component to use in React Native.

React Native

Probably almost everybody has already heard about React Native, but if you have not, TLDR: it makes use of JavaScript and React but builds a native UI thanks to some clever bridge techniques.

You can find all about it in the project page.

If you generate a demo project by invoking react-native init, you will get a working skeleton, which is the one I will base the post on.

Let’s attempt to extend it by adding a simple ProgressBar. This is already implemented as part of the standard React Native distribution, but will serve us as an easy sample.

Android side

Extensions to the existing bindings are made by implementing the ReactPackage class. It can be done in three different ways:

1. Native Modules

They provide an inteface for JavaScript code to call native Java methods. For instance, exposing the Toast API as done in the documentation examples.

C++ native modules are provided in a different way, so they can be fully cross-platform.

2. JavaScript Modules

Basically the opposite way around: When you call on a method of a class implementing this interface, the equivalent will be called on the JavaScript realm.

3. ViewManagers

Native views are provided through implementations of the ViewManager class, responsible of instantianting and updating views of a given type. This is the one we are interested in for now.

Since we are only setting up a native view component, we will need to go from the ViewManager all the way up through several layers.

The ViewManager

All ViewManager instances need to report two things: a name to be mapped to a React class, and a way to create an instance of the view they manage. For our ProgressBar example, this is quite easy.

public class ProgressBarViewManager

extends SimpleViewManager<ProgressBar> {

public static final String REACT_CLASS = "ProgressBar";

@Override

public String getName() {

return REACT_CLASS;

}

@Override

protected ProgressBar createViewInstance(

ThemedReactContext reactContext) {

return new ProgressBar(reactContext);

}

}

Here, ThemedReactContext is just a wrapper on top of the Android Context we all know (and perhaps hate).

With this done, React Native is able to instantiate a ProgressBar each time it finds the JSX tag for it.

The Package

At the package level, we do not need to return anything but our brand new ViewManager

@Override

public List<ViewManager> createViewManagers(

ReactApplicationContext reactContext) {

return Collections.<ViewManager>singletonList(

new ProgressBarViewManager()

);

}

The rest of methods can return empty collections safely for now, since we do not need anything from them.

The entrypoints: ReactNativeHost

The boilerplate output of react-native init generates a subclass of ReactApplication (generally MainApplication). This wires the native Android calls down to the library. We need to add the new package to the list of packages reported to the JavaScript side, and we are more than done with Java world. This is done in the getReactNativeHost() method, but we usually declare a field for it:

ReactNativeHost mReactNativeHost = new ReactNativeHost(this) {

@Override

public boolean getUseDeveloperSupport() {

return BuildConfig.DEBUG;

}

@Override

protected List<ReactPackage> getPackages() {

return Arrays.<ReactPackage>asList(

new MainReactPackage(),

new ProgressBarPackage()

);

}

};

JavaScript (React) side

This step is quite simple, since most of it is handled by the React and React Native code. The only thing left for us to do is to describe the propTypes and export the module.

'use strict';

import {

NativeModules,

requireNativeComponent,

View

} from 'react-native';

var iface = {

name: 'ProgressBar',

propTypes: {

...View.propTypes // include the default view properties

},

};

var ProgressBar = requireNativeComponent('ProgressBar', iface);

export default ProgressBar;

You might be wondering what are those default view properties. Since we inherited SimpleViewManager (which extends BaseViewManager) when creating our own ViewManager, we can take advantage of that to have all the basic mappings from CSS to View properties solved for us. Those include properties such as opacity, backgroundColor and flex. Full list available here.

What if we want to expose our own? Well…

Exposing view properties

In the Java side, we need to create our setters in the ViewManager implementation and annotate them with @ReactProp. There we note the name of the property coming from JSX world, and optionally we can define a default value.

@ReactProp(name = "progress", defaultInt = 0)

public void setProgress(ProgressBar view, int progress) {

view.setProgress(progress);

}

@ReactProp(name = "indeterminate",

defaultBoolean = false)

public void setIndeterminate(ProgressBar view,

boolean indeterminate) {

view.setIndeterminate(indeterminate);

}

This setter will be called every time the property of our React component is updated. In case of the property being removed, then the default value is used.

Then, we need to add it to the React Native interface. Back in the js file, at our module’s iface we should describe the properties we exposed in the ViewManager, both with name and type.

var iface = {

// ...

propTypes: {

progress: PropTypes.number,

indeterminate: PropTypes.bool,

},

// ...

};

This way, both native and React sides will speak in the same terms. In the end, our module’s JS file would look something like this:

'use strict';

import { PropTypes } from 'react';

import {

NativeModules,

requireNativeComponent,

View

} from 'react-native';

var iface = {

name: 'ProgressBar',

propTypes: {

progress: PropTypes.number,

indeterminate: PropTypes.bool,

...View.propTypes // include the default view properties

},

};

var ProgressBar = requireNativeComponent('ProgressBar', iface);

export default ProgressBar;

All together

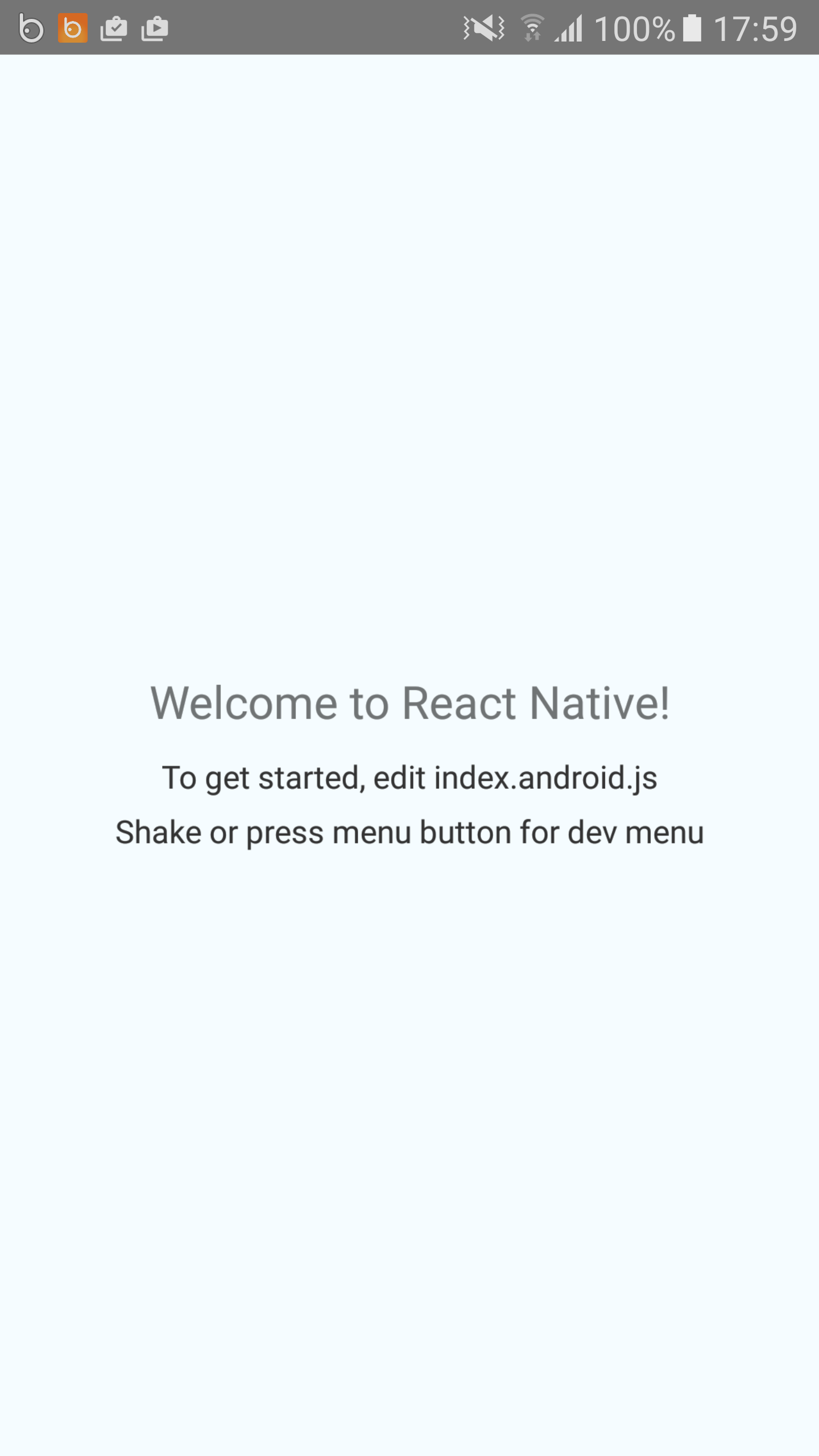

Kickstart the react-native server, deploy the APK to your favourite emulator or real device, and if nothing is missing the million gear machine will produce something that looks more or less like this.

Aftermath

React Native, more than a year after its public release (and not even one after the Android release), is in a way more mature state than the last time I attempted anything on it. You can have a working boilerplate project with one command. Docs are very helpful and community content is great.

However, it still feels very cumbersome to integrate it with complex modules.

There is, nevertheless, an alternative approach. Instead of having a brand new React Native application adopt native components, there is the possibility of doing the complete opposite - having a mature production application integrate one simple React Native component.

From reading the docs, it looks more complicated than it sounds, and I have some concerns about the build process - speed and reliability. But that’s food for another thought, and most likely another post. Stay tuned!